Nickerson House

Nickerson, Samuel, House | |

Samuel M, Nickerson House | |

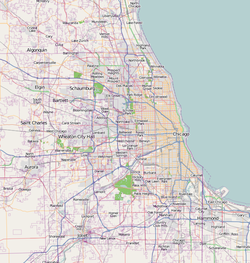

| Location | Chicago, IL |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 41°53′38.28″N 87°37′36.36″W / 41.8939667°N 87.6267667°W |

| Built | 1883 |

| Architect | Burling & Whitehouse; Burling, Edward |

| Architectural style | Late Victorian |

| NRHP reference No. | 76000700 [1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | November 7, 1976 |

| Designated CL | September 28, 1977 |

The Samuel M. Nickerson House, located at 40 East Erie Street in the Near North Side neighborhood of Chicago, Illinois, is a Chicago Landmark. It was designed by Edward J. Burling of the firm of Burling and Whitehouse and built for Samuel and Mathilda Nickerson in 1883. Samuel M. Nickerson was a prominent figure in the rising national banking industry, who was said to have owned at one point more national bank stock than anyone else in the United States.[2]

In 1916, in an early act of historic-building preservation, a group of wealthy Chicagoans bought the house and donated it to the American College of Surgeons (ACS). In addition to using the house as its headquarters, ACS built the adjacent classical Murphy Memorial Auditorium for meetings. When the mansion became too small for the ACS, it began renting it out in 1964. The house is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and was bought in 2003 by philanthropist Richard Driehaus. It is home to the Richard H. Driehaus Museum, which focuses on architecture of the Gilded Age, the Art Nouveau movement.

Architecture

[edit]The Nickerson House was designed by one Chicago's earliest prominent architects, Edward J. Burling (1819–1892) of Burling and Whitehouse.[3] In addition, three decorators were contracted for the interiors: William August Fiedler (1843–1903) and R. W. Bates & Co. of Chicago, and New York-based George A. Schastey & Co. The three-story, 24,000 square-foot Nickerson House was reported to be the largest and most extravagant private residence in Chicago at the time of its completion. (This distinction would be transferred to the Palmer Mansion on the Gold Coast several years later.) Nickerson spared no expense, spending $450,000 on the construction and decoration of his home.[4]

The mansion's Italianate exterior is limestone and Ohio sandstone.[5] Although elegant, the restrained design of the façade belies the wealth of detail found within. The house's interiors are decorated with a large amount of marble (17 types, giving it the nickname of the "Marble Palace"), onyx, alabaster, carved and inlaid wood, glazed and patterned tiles by Minton Hollins & Co. and J. & J. G. Low Art Tile Works, mosaics, and Lincrusta.[6]

With a majority of its original features intact, the building today is a well-preserved example of the Aesthetic Movement as translated into the design of homes for wealthy Americans in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This is seen in the wide variety of highly ornamented styles stemming from Japanese, Chinese, English, French, Moorish, ancient Greek, Renaissance Italian, and other influences. With its profusion of motifs and materials, the Nickerson House is indicative of the Victorian love for display as well as the general architectural mood emerging in Chicago in the years before the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition.

-

Dining Room, 1886.

-

Reception Room, 1886.

-

Samuel M. Nickerson's Bedroom, 1886.

Fireproofing

[edit]Construction on Nickerson House began in 1879, shortly after the 1871 Great Chicago Fire and the resulting development of city ordinances for the fireproofing of masonry structures. The mansion was lauded as one of the first truly fireproof residences in the city. The masonry is brick, with partition walls carried up to the roof. Beneath the highly decorative flooring boards are flooring strips bedded in mortar, followed by brick arches supported by iron beams.[7]

History

[edit]The house was commissioned by Samuel Mayo Nickerson, one of the founders of the First National Bank in Chicago and Union Stockyards National Bank, as well as having interests in liquor and wine businesses and an explosives company during the Civil War. Samuel Nickerson hailed from Brewster, Massachusetts on Cape Cod, where his family was instrumental in the development of the area's commercial shipping and fishing. The Nickerson Family first settled on Cape Cod in 1640.[8] Samuel Nickerson also constructed Brewster's Gilded Age masterpiece, Fieldstone Hall, in 1890.[9]

Nickerson, his wife Mathilda Pinkham Crosby, and their son Roland lived in the house from 1883 to 1900. The mansion was used for many social gatherings characteristic of the Gilded Age, including a masquerade ball and a number of receptions. It also served as exhibition space in which the Nickersons displayed their renowned art collection of American and European paintings and drawings, Indian jewelry, and Japanese and Chinese ivories and curios. In 1900 the Nickerson Collection was donated to the Art Institute of Chicago.[10]

After the Great Fire, the Near North Side became a fashionable neighborhood for prominent Chicago business owners like Nickerson. Because the area was home to Cyrus H. McCormick, his brothers William S. McCormick and Leander J. McCormick, and their descendants, whose mansions were mainly concentrated along Rush Street, the neighborhood was known as McCormickville. Other notable residents of the Gilded Age period include Ransom R. Cable, Lambert Tree, Perry H. Smith, Joseph T. Ryerson, and Edward T. Blair.

Upon retiring from his position as president of the First National Bank of Chicago in 1900, Nickerson sold the house to Lucius George Fisher, the president of Union Bag & Paper Co., who owned the house until his death in 1916.[11] After purchasing the house, Fisher hired the Prairie School architect George Washington Maher to redesign Nickerson's art gallery, making it into a trophy room and rare book library. Among other features, Maher had a stained glass dome built to replace the room's skylight. As part of the remodeling, new book cases and a monumental mantlepiece, attributed to Robert E. Seyfarth who was an architect in Maher's office at the time, were installed in the gallery. The iridescent glass tile fire surround of the mantle was created by the Chicago firm of Giannini & Hilgart.

The family's decision to sell the mansion after Fisher's death in 1916 sparked what is believed to be Chicago's first successful preservation effort.[12] After the house remained on the market for three years without a buyer, a group of prominent Chicagoans, including Cyrus Hall McCormick II, William Wrigley, Jr., and Julius Rosenwald, were concerned about the possible demolition of the magnificent residence. The group raised the money to purchase the house as a civic effort, and in 1919 presented the deed to the American College of Surgeons. This gift spurred the College of Surgeons' decision to make Chicago its headquarters. From 1919 to 1965, the organization utilized the former Nickerson residence as administrative offices and meeting rooms.[4]

Museum

[edit]The house was acquired by Chicago businessman Richard Driehaus in 2003 who has since restored and opened the property to the public as the Richard H. Driehaus Museum in 2008. The rooms display some furnishings original to the Nickerson period as well as Driehaus' private collection of late 19th and early 20th-century decorative arts objects, including a large private collection of statues, paintings, furniture, and Louis Comfort Tiffany glass.[13]

Restoration

[edit]When the restoration began in 2003, the building itself was deemed in good condition. It was, however, very dirty. One of the most noteworthy elements of the restoration focused on cleaning the exterior. The facade is predominantly porous sandstone, which over the years had accumulated a thick crust of grime and pollutants. The formerly light gray stone had become a deep, dark black. Traditional methods to blast away or clean the pollutants with chemicals were deemed unsuitable, and the exterior was cleaned by lasers. This was the first time an entire building had been cleaned using this method in United States, although it is commonly utilized in Europe for cleaning sculptures.[5]

The restoration, which transformed the old Nickerson House into the Richard H. Driehaus Museum, won a Chicago Landmark Award for Preservation Excellence in 2008.[14]

References

[edit]- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- ^ Chicago Daily Tribune, July 21, 1914. "S. M. Nickerson Expires in East: Pioneer Banker of Chicago Dies in East Brewster, Mass, at Age of 84." p. 7

- ^ "Chicago Landmarks: Burling Row House District". City of Chicago Department of Housing and Economic Development, Historic Preservation Division. 2000. Retrieved 2013-04-23.

- ^ a b Historic American Buildings Survey (June–July 1967). Samuel M. Nickerson House, 40 East Erie Street, Chicago, Cook County, IL (HABS IL-1052 ed.). Library of Congress.

- ^ a b Kahn, Eve M. (October 2008). "Kaleidoscope Palette". Traditional Architect. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ^ "Chicago Landmarks: Nickerson House". City of Chicago Department of Planning and Development, Landmarks Division. 2003. Archived from the original on 2007-06-24. Retrieved 2007-06-25.

- ^ "Residence of Samuel M. Nickerson; Burling and Whitehouse, architects". American Architect, IX. February 26, 1881. p. 103.

- ^ commint (2013-03-29). "William and Anne (Busby) Nickerson Come to Town". Nickerson Family Association. Retrieved 2023-10-18.

- ^ "A Crown Jewel of Cape Cod". CapeCod.com. 2023-03-02. Retrieved 2023-10-18.

- ^ "Gift to the Art Institute: Mr. and Mrs. S. M. Nickerson Present Their Collection". Chicago Daily Tribune. January 26, 1900. p. 1.

- ^ White, James Terry (1910). The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography. J. T. White Company. p. 119.

lucius george fisher.

- ^ Sharoff, Robert (October 2007). "A Classic Act". Chicago Magazine. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ^ "Driehaus Museum opens: Modernists need not enter". Time Out Chicago. May 14, 2008.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Cosgrove, Suzanne (September 7, 2008). "Recognition of 22 jobs well done". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 24 April 2013.